Probeta Mag had the opportunity to know more about FEAT, a European project which aim was bringing together artists and research projects, at the Ars Electronica Festival 2017. Developed in the framework of the Future and Emerging Technologies funding programme of the European Commission, the core idea was to pair experienced artists with a set of FET projects hoping to facilitate the communication of leading-edge research and technology with a broad public and to stimulate technology take-up and ultimately innovation.

The FEAT project supported six funded residencies of experienced artists and initiated two more residencies without financial support from FEAT. The artists were tasked with delivering artworks after a period of about nine months during which they visited one or several research sites, e.g. laboratories. Often the scientists dedicated special attention to the presence of the artist, e.g. by organising workshops or dedicating a full day of discussion between the artists in residence and the scientists and engineers working on the project. The FET technology projects covered areas as diverse as robotics, synthetic biology, quantum physics, chemistry and supercomputing. Artists become early adopters of technology based on their acquisition of new competencies and experimentation with research technology.

Erich Prem, RTI strategy advisor and CEO of eutema GmbH, who works scientifically in artificial intelligence, research politics, innovation research and epistemology, coordinator of FEAT. Probeta Mag talked with him how the multiplicity of approaches to the experimental tools of the science and the contemporary art, contributed to boost the impact for technology-oriented research projects with important long-term effects in the society by means of the materiality of artworks.

What was the starting point for creating the FEAT project?

The first idea came in response to the European Commission’s insight that we need to do more in Europe to put the outstanding results of science to innovative and creative use. The so-called ‘European paradox’ describes a situation where Europe is very good at doing science, but not very good at turning it into economic success stories. Although this storyline is contestable, we wanted to stir creativity with the help of artists. From a more general perspective, you may as well say that science and the arts were once one, and have only become separated in the course of specialisation.

There have also been some initiatives that tried bringing artists and scientists closer together, for example the ICT & Art Connect initiative of the EU, which was funded under the Seventh Framework Programme. However, there are two important differences with FEAT: firstly, while there have been several cases where artists took inspiration from science, there has been little focus on inspiring science and technology from an artistic perspective. Of course, art has inspired science many times in the past, such as research based on the work of science fiction authors and filmmakers, and of course in many single instances where scientists took inspiration from works of art, but these were isolated incidents. In a more systematic form, it is rather new. Secondly, FEAT aims to establish a longer work relationship between artists and scientists to give both sides sufficient time to elaborate concepts, develop new perspectives and ask novel questions without the huge pressure to deliver something over the course of a short workshop.

What is the European Commission’s perception of the discourse between experimental art and experimental science?

Nowadays there is an increasing number of science and technology programmes that invest in artists, e.g. the European Commission’s STARTS initiative in the Framework Programme for Research “Horizon 2020”. The explicit rationale is to increase the impact of scientific work, foster new ways of thinking, and stimulate innovation emerging from art/science cooperation. Simply put, artists can help technology development by bringing novel viewpoints into research projects and disseminate the results to a broader audience and therefore support the take-up of new technologies. The arts, by their pure investigative nature, can initiate innovations that other actors develop further because artists may not have an interest in innovation as such. Instead, they may aim to produce ‘meaning’. In this way, artists play a central role not just in designing potential forms of usage of new technologies, but focus on the deeper questions of giving meaning to technology. This can result in social innovation as a particularly interesting outcome of many art/science interactions.

How were FET projects and artists selected?

We contacted all FET projects that had started around the same time as FEAT as we wanted the artists to participate from an early project stage and were generally surprised about the very positive responses we reviewed. In the end, 18 projects decided to send representatives to our matchmaking workshop in Amsterdam, where we brought together the artists and the research projects.

As for the artists, a call was disseminated through various channels and we received an overwhelming amount of responses. In total, there were 264 submissions. All of them were judged by the consortium based on three criteria: artistic quality, executive quality, expected collaboration with FET projects and expected societal impact. The twelve best artists were then shortlisted and evaluated by our advisory board who had the final say in the five wining artists. Finally, at the matchmaking workshop each of the participating research projects and artists presented their work. Due to the high number of interested FET projects, we were able to let the artists chose what project they wanted to work with.

During the open talk in Ars Electronica where the FEAT participating artists share their experiences with the public, it was discussed that the artists were seen as a “burden” in the lab. What have been the lessons learnt? Is there a need for trust building in the scientific field when talking about interdisciplinary experiences?

There was indeed the fear, that the artists would be seen as a “burden” in the laboratories. However, this fear did not substantiate whatsoever. It turned out scientists were excited about the interaction with artists liberating them from their daily lab routine, permitting a fresh look at their own work, and allowing them to devote explicit time for less goal-focused deliberation that is usually difficult to achieve given project deadlines. They reported that the artists forced them to think outside the box, fostering creativity and innovation.

It surely was important though, to have artists in the project who have scientific backgrounds and a solid understanding of the projects that they were working with. Identification, selection, and coupling of the artist and the FET project was based upon affinity and interests of the artists in the specific FET area. This aimed at a strong interaction between artists and scientists to facilitate an early development of trusted relationships. Such mutual trust is not always easy to develop, but important for a creative working environment and for very practical reasons including for example scientists granting the artists access to all data.

At what extent was the society involved in this interdisciplinary dialogue?

Societal feedback was gathered mostly through our two public workshops, both held at the Ars Electronica Festivals 2016 and 2017 respectively. At these events, the audience was introduced to results of the project and given an overview of artist’s and researcher’s experiences. Other stakeholders like policy makers, curators and scholars were also invited to join in order to facilitate a broader discussion and include as many different viewpoints as possible. Finally, these expert panels would always cumulate in an open exchange with the audience where we would ask questions like “are we doing this right”?

Generally, the broad public was constantly kept up to date on the project’s progress not only through articles, videos and podcasts, but also through responsive channels like Facebook, Twitter and Youtube, where it is possible to start a dialogue on the project and its implications.

How do you see the future of these interdisciplinary collaborations? A second part of the FEAT project has been put in place?

As we have garnered a lot of very positive feedback from both artists and researchers, we are sure that there will be more projects like FEAT in the future. As for the FEAT artists, many of them will continue working with their respective FET projects after the project has officially ended. While there is no specific second part of FEAT planned, the consortium has decided to keep the project going in another way, by offering the service of bringing artists into interested research projects.

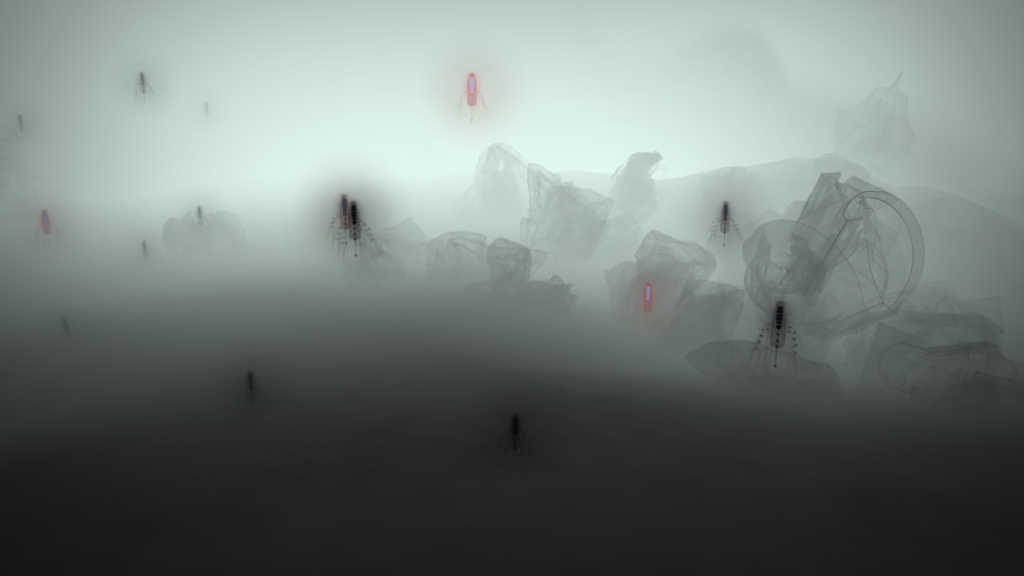

Cover image: «Ion Hole» by Evelina Domnitch & Dmitry Gelfand: based in quantum simulators with Rydberg atoms.